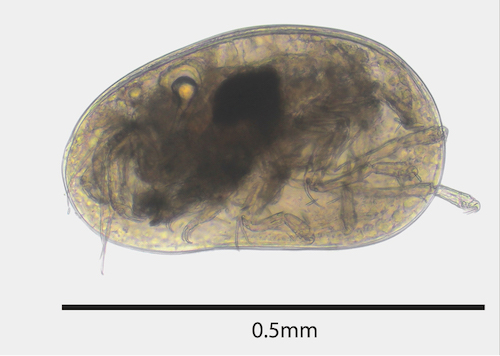

1. Ostracods produce spermatozoa with the largest volume in the animal kingdom. More....

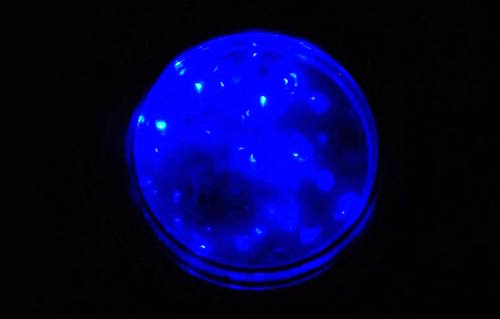

1. Ostracods produce spermatozoa with the largest volume in the animal kingdom. More....2. Some marine species produce a bright, blue light (bioluminescence). More....

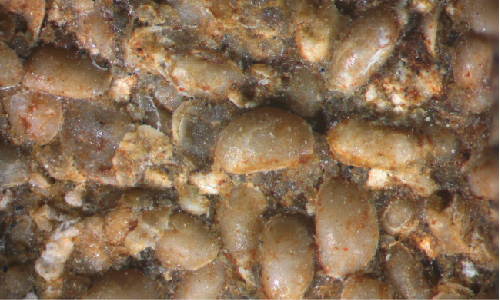

3. With a fossil record stretching back almost 500 million years, ostracods are the most abundantly preserved arthropod in the fossil record. More....

4. The oldest known fossil penis belongs to an ostracod 425 million years old. More....

5. Many species reproduce without sex by cloning themselves. More....

6. Some species live on the gills of other crustaceans, such as crayfish. More....

7. Their eggs can survive complete drying and be viable many years later. More....

8. The wind, birds and toads all help ostracods get around. More....

9. They can survive being eaten by fish. More....

10. Some species can survive out of water by taking a small supply of water with them in their shells. More....

11. By attacking in groups, ostracods can prey on animals much larger than themselves. More....

12. Ostracods can learn. More....

1. Giant sperm

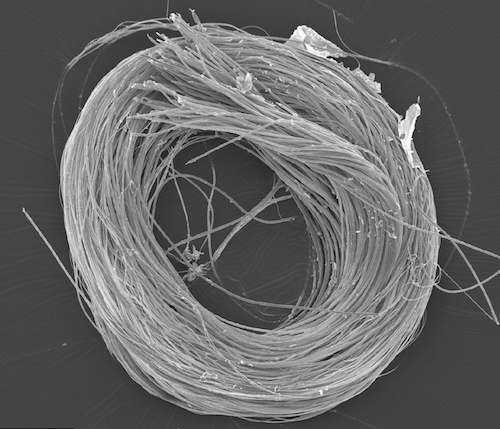

Ostracod sperms of the group Cypridoidea are massive, at least one-third the length of the corresponding males, and often much longer. The longest belongs to the Australian species Australocypris robusta, reaching 11.7 mm in length, 3.6 times the length of the male.Some insects have longer sperms, notably the fruit fly Drosophila bifurca, the sperms of which can reach 58 mm in length. But ostracod sperms are much thicker, so the corresponding volumes are much greater; the volume of a single sperm of the ostracod Australocypris robusta is nearly six times greater than that of the fruit fly Drosophila bifurca. Additionally, while the sperms of Drosophila bifurca consists almost entirely of very long flagella, ostracod sperms have no flagella at all. Each sperm consists of an extremely stretched out nucleus, wrapped for a lot of its length by two giant mitochondria.

Giant sperms of Australocypris robusta. The male stores the sperms by coiling them into a ring.

Back

2. Bioluminescence

Known in Japan as umi-hotaru (sea-fireflies), some species of Myodocopida ostracods produce a bright blue light. At night in many places in the world (e.g. Japan, the Carribean, Australia) the flashes of light can be observed in the water. The light is produced by mixing two chemicals together in the presence of oxygen and is for mating displays. Different species flash at different rates, to stop any confusion in the dark.During the second world war the Japanese army collected umi-hotaru in baited traps, dried them out and ground them down to a powder. On the battlefield at night a small amount of water was added to the powder to produce a low intensity light, used to read orders or maps without giving their position away to the enemy.

- References:

- ⚬ Cohen, A. C. and J. Morin 2003. Sexual morphology, reproduction and bioluminescence in Ostracoda. In: L. E. Park and A.J. Smith (eds.) Bridging the Gap: Trends in the Ostracode Biological and Geological Sciences. The Paleontological Society Papers 9:37-70. New Haven: Yale University Press.

- ⚬ Morin, J. G. and Cohen, A. C. 1991. Bioluminescent displays, courtship, and reproduction in ostracodes. In R. Bauer and Martin, J. (Eds.), Crustacean Sexual Biology:1 16. New York:Columbia University Press.

3. Most abundantly preserved arthropod in the fossil record

The first fossil ostracods are recognized from rocks of the Ordovician Period, 485 to 443 million years ago. Due to their calcitic carapace, ostracods have a high fossilization potential, and this combined with their high diversity and wide range of habitat preferences resulted in them becoming the most abundantly preserved arthropod in the fossil record. This makes ostracods very useful for palaeontologists, as they can be used for stratigraphical and palaeo-environmental (i.e. depth, temperature, salinity) indicators.- References:

- ⚬ Whatley, R. C., Siveter, D. J. and Boomer, I. D. 1993. Arthropoda (Crustacea: Ostracoda). 343-356. In Benton, M. J. (ed.) The Fossil Record 2. Chapman and Hall, London, 827pp.

4. The oldest known penis

The oldest known fossil penis belongs to the ostracod Colymbosathon ecplecticos, discovered from rock 425 million years old in England. A wide variety of animals living in the sea 425 million years ago were killed by an ash fall from a volcanic eruption. The ash preserved the animals, including their soft parts (bits that usually rapidly decay). Painstaking 3-D reconstructions of a preserved male ostracod revealed amazing details such as the hairs on limbs, gills and a penis.

- References:

- ⚬ Siveter, D. J., Sutton, M. D., Briggs, D. E. G. & Siveter, D. J. 2003. An ostracod crustacean with soft parts from the Lower Silurian. Science, 302, 1749 - 1751.

5. Cloning

Many freshwater ostracods reproduce without sex (asexuals) by cloning themselves. This is called parthenogenesis and is thought to be caused by a parasitic bacteria that infects the eggs. Such species consist of all female populations. Some species (e.g. Dolerocypris ikeyai) show geographic parthenogenesis, with sexual populations in a few isolated places and asexual populations elsewhere.There are some short term advantages to asexual reproduction, for example, no time or energy is wasted producing males or searching for a mate and only one individual is needed to start a new population, so such species can spread quicker than their sexual counterparts. However, in the long term reproduction without sex can cause genetic mutations to build up and asexual populations are considered more likely to become extinct in the long term.

- References:

- ⚬ Martens, K. (ed.). 1998. Sex & parthenogenesis. Backhuys Publishers, Leiden, 335 pp.

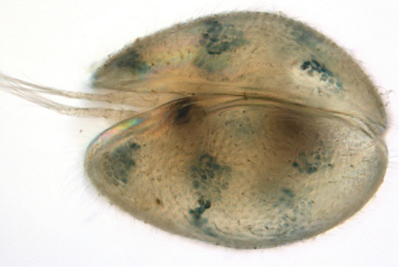

6. Living with other crustaceans

Consisting of about 220 species, the family Entocytheridea is a diverse group which lives on other crustaceans. With their tiny size and narrow shells, they are ideally suited to living in the tiny spaces on the gills and thoraxes of crayfish, amphipods and crabs. They have specially adapted thoracic limbs and antennae to grab hold of their hosts. Although the exact relationship between the entocytherids and their hosts is not clear, it is thought that in return for a safe place to live, the ostracods help to keep the bodies of their hosts clean.- References:

- ⚬ Hart, D. G. & C. W. Hart, Jr, 1974. The ostracod family Entocytheridae. Natul. Nat. Acad. Nat. Sci. Philadelphia, Monograph 18: 1- 239.

7. Tough eggs

Many freshwater ostracods can be found in temporary water bodies, such as puddles and rice fields. The secret to their survival in such temporary habitats is because their eggs can be viable many years after being dried. When water is available the eggs start to develop and hatch.Georg Ossian Sars (1837 - 1927), a famous Norwegian crustacean worker, used this ability to study ostracods from the other side of the globe. People in South Africa and Australia sent him dried sediment that they had collected from dried up ponds or rivers. By adding water to the dried sediment and waiting for a few weeks, Sars raised ostracods, many of them new species that he later named and described.

- References:

- ⚬ Sars, G. O. 1895. On some South-African Entomostraca raised from dried mud. Skrifter i Videnskabs-selskabet. I. Mathematisk-Naturvidenskabs Klasse 1895 (8): 1-56.

- ⚬ Sars, G. O. 1896. On some west Australian Entomostraca raised from dried sand. Arch. Math. Naturv. 18, 1-35.

8. Hitching a ride

Ostracods are found in almost every aquatic habitat, even some very small and isolated places such as the tiny pools of water in bromeliads growing on trees. Some species have a global distribution and are found from the subarctic to the tropics. Their distribution in part is due to their dispersal abilities. The eggs are tiny and can survive complete drying (see 7) and can therefore be blown great distances by the wind. The eggs and adults can also hitch a lift on the feet of birds - the long migrations of arctic terns are thought to explain the distribution of one species, Potamocypris humilis, that is found in Northern Europe and South Africa. Another species, Cyclocypris ovum is known to attach itself to the skin of toads and can therefore be transported from pond to pond.- References:

- ⚬ Horne, D. J. & Smith, R. J. 2004. First British record of Potamocypris humilis (Sars, 1924), a freshwater ostracod with a disjunct distribution in northern Europe and southern Africa. Bollettino della Societe Paleontologica Italiana, 43 (1-2), 297-306.

- ⚬ Laessle, A. M. 1961. A micro-limnological study of Jamaican Bromeliads. Ecology, 42, 499-517.

- ⚬ Seidel, B. 1989. Phoresis of Cyclocypris ovum (Jurine) (Ostracoda, Podocopida, Cyprididae) on Bombina variegata (L.) (Anura, Amphibia) and Triruris vulgaris (L.) (Urodela, Amphibia). Crustaceana 57, 171-176.

9. Survive being eaten

Fish eat ostracods, sometimes in great numbers. However, the fish don't get it all their own way. Experiments with the ostracod Cypridopsis vidua showed that 26% of specimens eaten by small bluegill sunfish came out the other end alive and unharmed. By tightly closing their shells and waiting they survived passage through the gut of the fish.- References:

- ⚬ Vinyard, G. 1979. An ostracod (Cypridopsis vidua) can reduce predation from fish by resisting digestion. American Midland Naturalist, 102, 108 - 190.

10. Moving out of water

All ostracods respire by extracting oxygen from water, but this hasn't stopped one group from venturing out onto dry land. The Terrestricytheroidea can walk over a dry surface by taking a small supply of water with them, in and around their shells. Special hairs on the shells help to retain the water and drag it along with them. However, if the ostracods are unable to replenish this water before it evaporates they perish.- References:

- ⚬ Horne, D. J., Smith, R. J., Whittaker, J. E. & Murray, J. W. 2004. The first British record and a new species of the superfamily Terrestricytheroidea (Crustacea, Ostracoda): morphology, ontogeny, lifestyle and phylogeny. Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society, 142, 253 - 288.

11. Attacking in groups

Ostracods may be small, but that doesn't stop them attacking animals much larger than themselves. Some myodocopid ostracods are ferocious predators and can bring down animals many times larger than themselves (e.g. annelid worms and fish) by attacking in groups. The ostracods attack the weakest parts of the animals first, such as around the mouth and anus, eating the victim alive. An attack can last many minutes until the victim is eventually killed.There is even a report of myodocopid ostracods attacking a diver; during a night dive in Panama, the diver's ears, hair and beard were covered with ostracods, forcing him out of the water.

- References:

- ⚬ Cohen, A. C. 1983. Rearing and postembryonic development of the myodocopid ostracode Skogsbergia lerneri from coral reefs of Belize and the Bahamas. Journal of Crustacean Biology, 3, 235 - 256.

12. Ostracods can learn

Ostracods can be trained to react to light stimuli, following a coloured light to a food source. This shows that these tiny animals exploit visual stimuli for decision making, and also for modulating their behaviour, swimming longer in presence of the right coloured light.- References:

- ⚬ Romano, D., Rossetti, G. & Stefanini, C. 2022. Learning on a chip: Towards the development of trainable biohybrid sensors by investigating cognitive processes in non-marine Ostracoda via a miniaturised analytical system. Biosystems Engineering, 213, 162-174.