Habitats

Seas and oceans. Ostracods live in the seas and oceans throughout the world, from the deep through to the shorelines, coral reefs, sea mounts and on many types of sediments, from gravels to mud. They can be found at all latitudes, from the tropics to the polar regions.

Most species are found living on the bottom, but some species are planktonic.

The deepest record of living ostracods with calcified carapaces is 9307 m (Brandão et al. 2019).

Photo: The English Channel, UK

Marine coastlines. Ostracods are common along coasts, in inter-tidal zones, rock pools and between the sand grains of beaches.

Many species of ostracods are associated with particular types of seaweeds.

Photo: The coast of Brittany, France

Brackish salt marshes and estuaries. Ostracods tend to be low diversity in brackish waters, such as in estuaries and salt marshes, but they can be very abundant.

There are some freshwater and marine species that can tolerate brackish water conditions, but other species are mainly or only found in brackish habitats.

Photo: Salt marshes, British Columbia, Canada

Lakes and ponds. Of the estimated 304 million natural lakes in the world (Downing et al. 2006), the vast majority are home to ostracods.

The highest records of living ostracods are from Pumayum Co, a lake at 5,030 m in Tibet (Peng et al. 2013; Fürstenberg et al. 2015)

Photo: Spirit Lake, Haida Gwaii, Canada

Ancient lakes. Although rare globally, ancient lakes are home to 25% of all non-marine ostracod species. Many of these species are endemic (Martens et al. 2008).

Photo: The ancient Lake Orhid, Macedonia / Albania

Man-made lakes, ponds and reservoirs. Due to their desiccant resistant eggs, many species of ostracods rapidly colonize man-made water bodies.

Photo: A man-made pond, Kusatsu, Japan

Rivers. In slow flowing rivers and streams ostracods can be abundant on and in the substrate and amongst water weeds.

In faster flowing rivers ostracods tend to live interstitially, i.e. in the spaces and gaps between sediment grains of the river bed and in gravel banks lining the rivers.

Photo: A river, Shiga Prefecture, Japan

Channels, ditches. Man-made channels and ditches are often colonized by ostracods. Even small drainage ditches along the edges of roads can be home to ostracods.

Photo: A man-made channel, Kanazawa, Japan

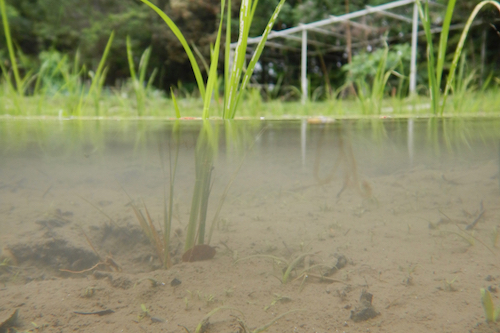

Rice fields. Rice fields are a major habitat for freshwater ostracods, and often ostracods are the most abundant animal group in such habitats. They can reach very high densities and influence the growth of the rice, both in positive and negative ways.

Many species of ostracods in rice fields, especially in Europe, are probably invasive, accidentally transported on farm machinery and rice plants. From rice fields they are able to colonize surrounding natural habitats (Valls et al. 2014).

Photo: Rice field, Shiga Prefecture, Japan

Wet leaf litter. Some ostracod species can utilize very small drops of water, and films of water in leaf litter and soils.

If moisture levels decrease too much, ostracods can enter a torpid state by tightly closing their carapaces. One species has been reported to survive over a year in soil with 4 to 5% water content this way (Horne 1993).

Photo: Wet leaf litter, Kanazawa, Japan

Springs and seeps. The discharges of small springs and seeps can harbour a diverse ostracod fauna. Some species are strongly related to such habitats, although can occasionally be found in other habitats too.

Photo: A spring, British Columbia, Canada

Caves. Ostracods can be found in cave systems, but diversity and abundance tend to be low. Sometimes typical surface-dwelling species opportunistically colonize caves, but there are a small number of species that are only known from such habitats.

In 2012 an ostracod species was discovered in a cave in South Korea that belonged to a genus thought to be extinct since the Eocene. It appears that this lineage moved from lake environments to caves at some point in the past (Smith et al. 2012).

Photo: A cave, Korea

Groundwater. The often vast and unseen groundwater habitats harbour diverse ostracod faunas. The groundwater fauna is very different to the species living in surface water bodies, with many species and genera only known from these habitats (e.g. Smith 2011). Many groundwater species are endemic to small regions.

Access to groundwater is limited to wells and boreholes, which means that sampling these habitats is restricted. Because of this, groundwater ostracod faunas are still poorly known in most parts of the world.

Photo: A well, Shiga Prefecture, Japan

References

Brandão, S. N., Hoppema, M., Kamenev, G. M., Karanovic, I., Riehl, T., Tanaka, H., Vital, H., Yoo, H. & Brandt, A. 2019. Review of Ostracoda (Crustacea) living below the Carbonate Compensation Depth and the deepest record of a calcified ostracod. Progress in Oceanography, 178, 102144.

Downing, J. A. et al. 2006. The global abundance and size distribution of lakes, ponds, and impoundments. Limnology and Oceanography, 51, 2388-2397.

Fürstenberg, S., Frenzel, P., Peng, P., Henkel, K. & Wrozyna, C. (2015) Phenotypical variation in Leucocytherella sinensis Huang, 1982 (Ostracoda): a new proxy for palaeosalinity in Tibetan lakes. Hydrobiologia, 751, 55–72.

Horne, F. R. 1993. Survival strategy to escape desiccation in a freshwater ostracod. Crustaceana, 65, 53-61.

Martens, K., Schön, I., Meisch, C. & horne, D. J. 2008. Global diversity of ostracods (Ostracoda, Crustacea) in freshwater. Hydrobiologia, 595, 185–193.

Peng, P., Zhu, L., Frenzel, P., Wrozyna, C. & Ju, J. (2013) Water depth related ostracod distribution in Lake Pumoyum Co, southern Tibetan Plateau. Quaternary International, 313–314, 47–55.

Smith, R. J. 2011. Groundwater, spring and interstitial Ostracoda (Crustacea) from Shiga Prefecture, Japan, including descriptions of three new species and one new genus. Zootaxa, 3140, 15-37.

Smith, R. J., Lee, J., Choi, Y. G., Chang, C. Y. & Colin, J-P. 2012. A Recent species of Frambocythere Colin, 1980 (Ostracoda, Crustacea) from a cave in South Korea; the first extant representative of a genus thought extinct since the Eocene. Journal of Micropalaeontology, 31, 131-138.

Valls L, Rueda J, Mesquita-Joanes F, 2014. Rice fields as facilitators of freshwater invasions in protected wetlands: the case of Ostracoda (Crustacea) in the Albufera Natural Park (E Spain). Zoological Studies, 53, 1-10.